Scientists Tell Their Story

The Science of the Neutrino

The neutrino is an extremely light, electrically neutral elementary particle, first proposed in 1930 by Wolfgang Pauli to explain the missing energy in certain radioactive decays. Pauli himself described it as a “terrible invention,” because this particle was almost impossible to detect.

It was only in 1956 that the neutrino was experimentally observed by Frederick Reines and Clyde Cowan, earning Reines the Nobel Prize in 1995.

In the 1990s, a major problem arose: scientists had a very good understanding of how the Sun works and the nuclear reactions producing neutrinos. The solar neutrino flux could be calculated very precisely. But when measuring this flux on Earth, only about half of the expected neutrinos were detected.

This discrepancy became famous as the “solar neutrino problem.” The theory of the Sun appeared solid, and the detection experiments were also reliable. The mystery stemmed from something new and unexpected in neutrino physics itself…

The Super-Kamiokande Detector

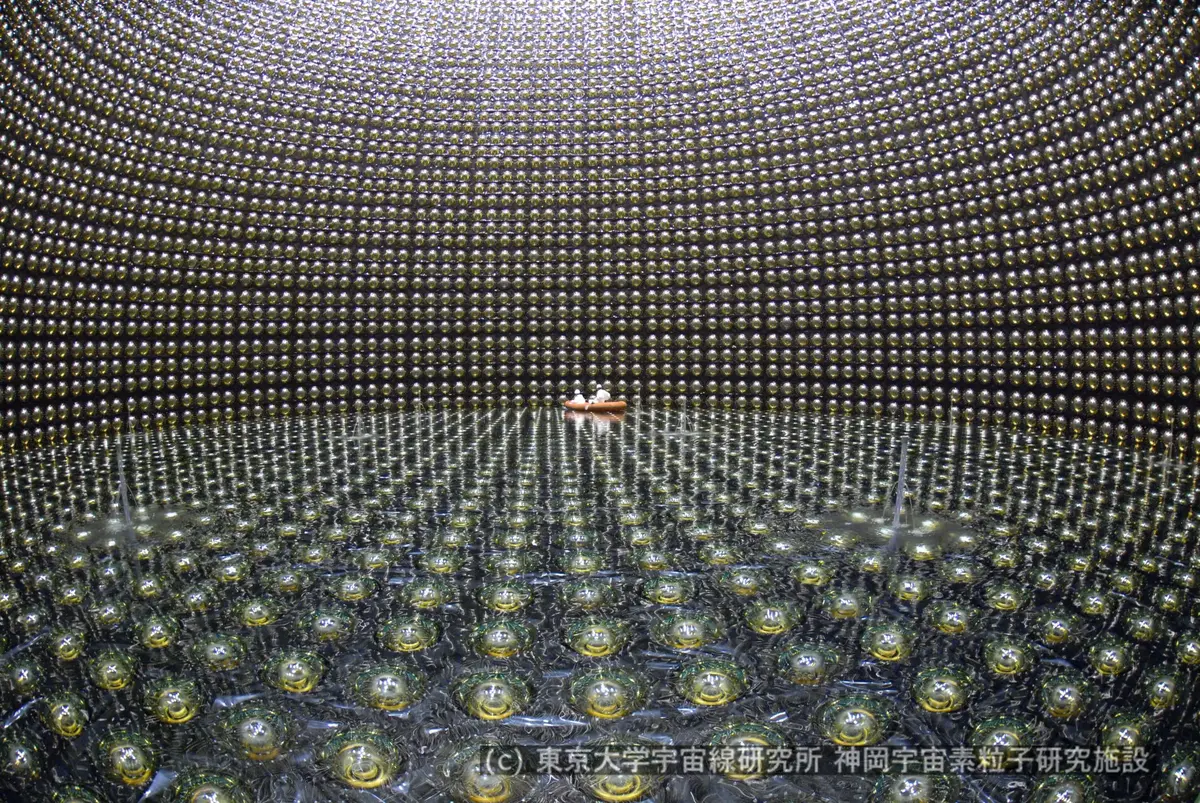

Super-Kamiokande is the successor to the Kamiokande detector, initially designed to observe the possible decay of the proton. Located 1,000 meters underground in Japan, it is a gigantic cylinder 40 meters in diameter and 40 meters high, filled with 50,000 tons of ultra-pure water.

Its walls are covered with more than 11,000 photomultiplier tubes—light-sensitive detectors capable of recording the extremely faint signals produced by neutrinos.

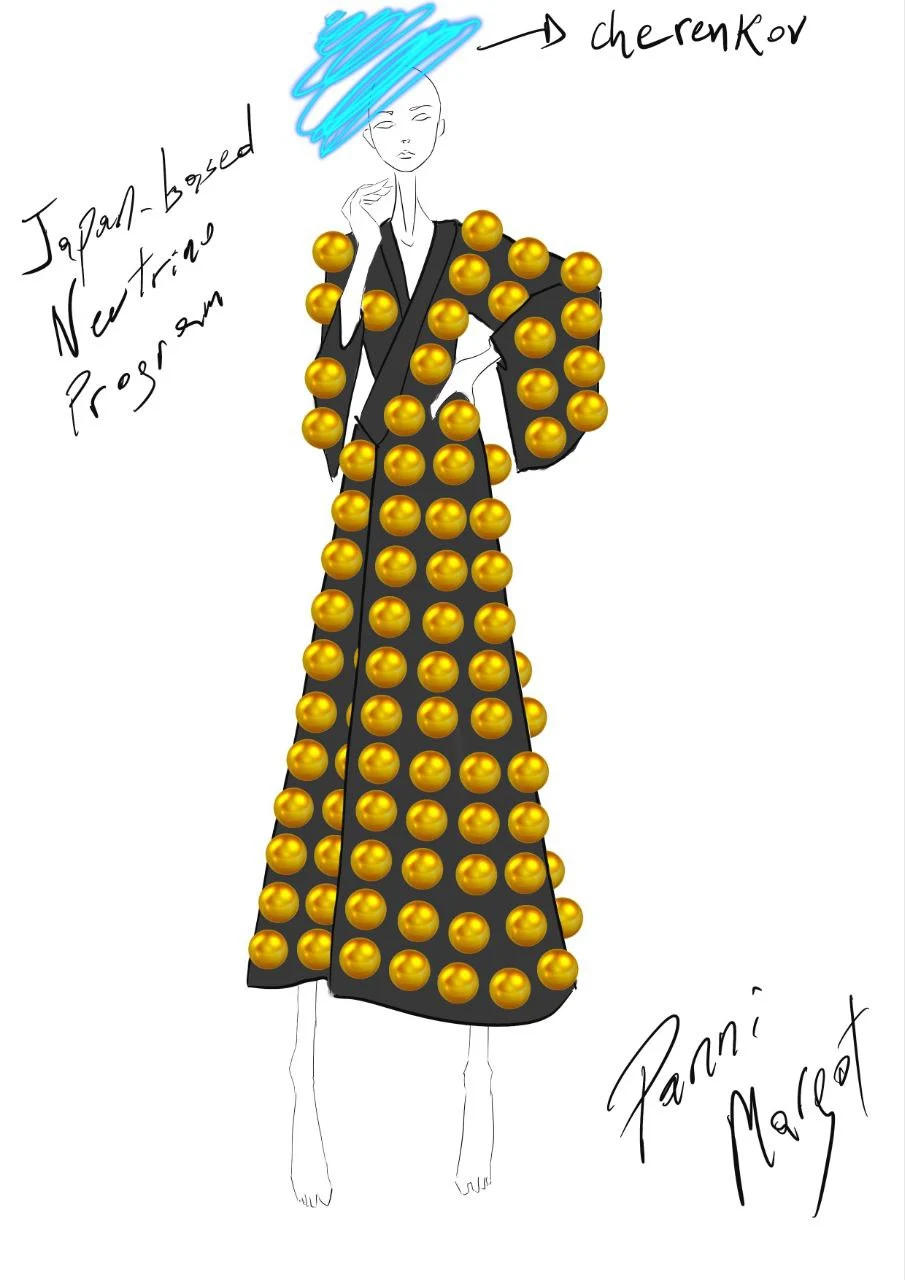

When a neutrino interacts with a water nucleus, it can produce a charged particle that moves faster than the speed of light in water. This particle emits a cone of light called Cherenkov radiation, which is recorded by the photomultipliers. The intensity and direction of this light allow scientists to reconstruct the energy and trajectory of the neutrino.

Unexpected Results and Nobel Prize

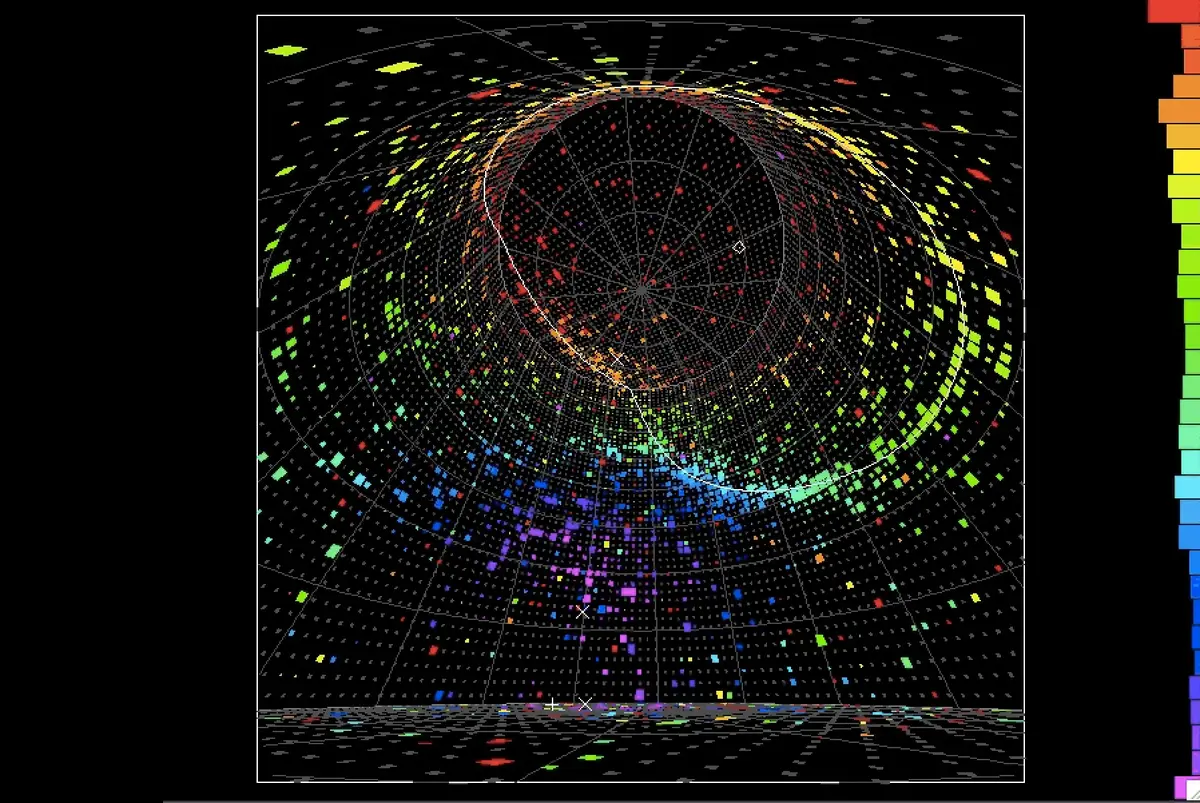

In addition to solar neutrinos, Super-Kamiokande can observe atmospheric neutrinos, produced by the interaction of cosmic rays with the atmosphere. These neutrinos are essentially of two types (called flavors): νμ (muon neutrinos) and νe (electron neutrinos). Theories predict a certain ratio between νμ and νe, and this flux can be measured precisely.

Super-Kamiokande discovered something unexpected: neutrinos coming from the sky (vertically downward) appear in the expected proportions, but the νμ neutrinos traveling through the Earth (from the opposite direction) are fewer than expected. This is not because they are absorbed by the Earth—very few are—but because νμ neutrinos oscillate into ντ over long distances, making them invisible to detectors sensitive only to νμ. Atmospheric νe neutrinos are practically unaffected.

This oscillation, confirmed by complementary observations at the Sudbury Neutrino Observatory (SNO) in Canada, was a major discovery in particle physics. It revealed that neutrinos have a non-zero mass, an unexpected property that earned Takaaki Kajita and Arthur B. McDonald the 2015 Nobel Prize in Physics, respectively for the observations at Super-Kamiokande and SNO.

Today, we are striving to deepen our understanding of neutrinos through ever more ambitious experiments, such as the future Hyper-Kamiokande detector, which aims to refine the measurement of their oscillations and mass differences.